The following section further argues that ACC and RCC had an almost symbiotic relationship – the company was the primary mover behind the increasing popularity of RCC’s image as a ‘modern’ and ‘revolutionary’ material in India, that ultimately resulted in a permanent alteration of the country’s built landscape. It delves into the formation and growth of ACC, its unique marketing techniques regarding this material, and why the company’s creation affected a significant change in the way India adopted RCC in its architectural language; it also discusses some of the drawbacks that resulted from this historic merger. Apart from reorienting the Indian cement industry, ACC’s innovative and vehement marketing strategies also built a consumer base where none existed before, thus cementing its reputation as a pioneer in advertising techniques in India.

Reinforced Cement Concrete (RCC) – The Modern Material of Possibility

“Ferroconcrete or reinforced cement concrete is a remarkable invention that is revolutionizing architectural design. Shapes entirely undreamt of in earlier materials… are not only possible, they are easy to make..You can support a huge building of ten or fifteen stories on four pillars if you want to, or stretch a railway roof across a dozen rail lines…such a span is hardly possible in any formerly known material.” [3]

– Charles Louis Fabri, An introduction to Indian architecture, 1963

Although cement had been in use for nearly 5000 years, Reinforced Cement Concrete or RCC was a modern innovation.[4] Originating in the second half of the nineteenth century, RCC emerged out of a need for a more economical and fireproof building material.[5]

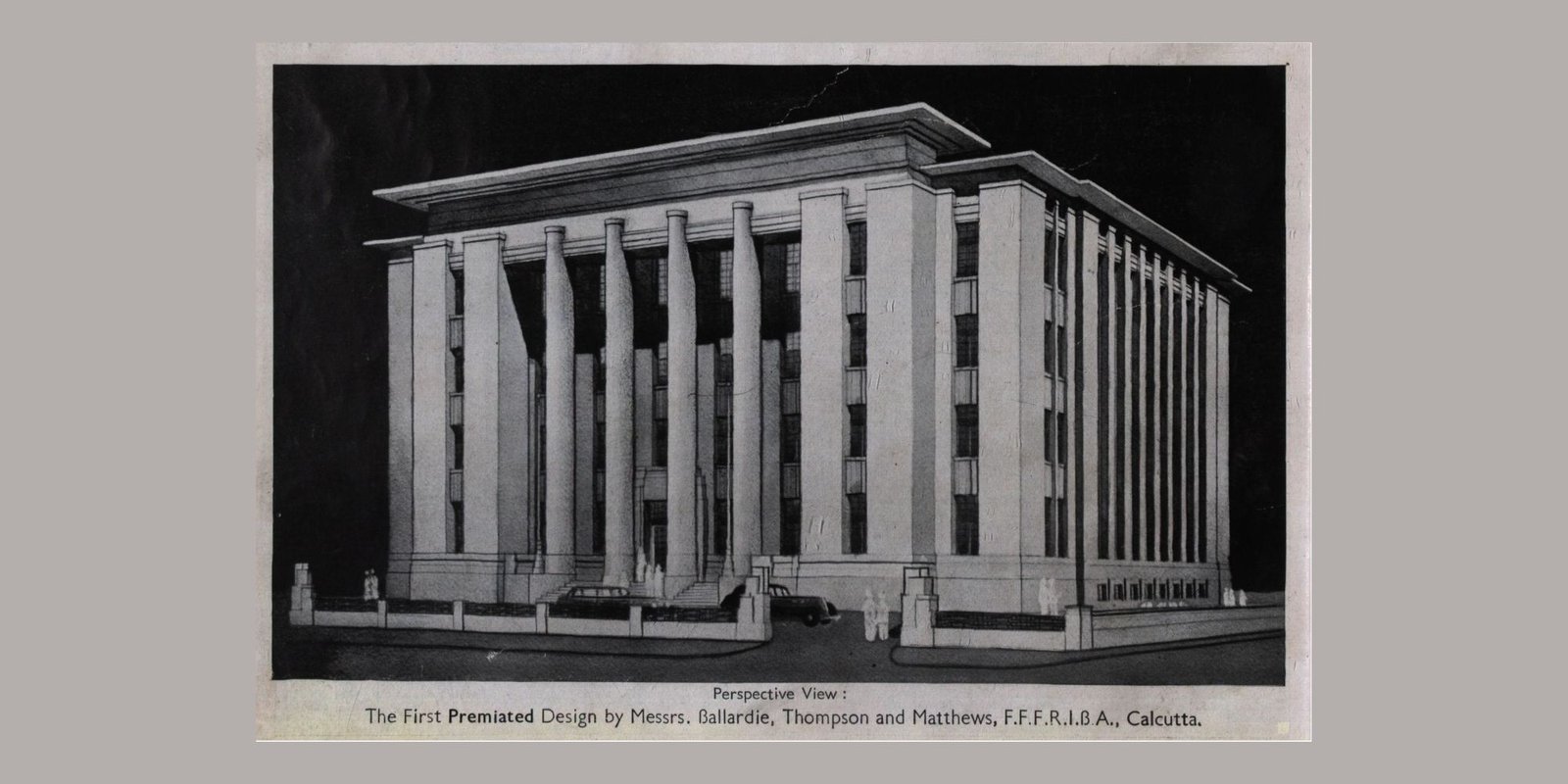

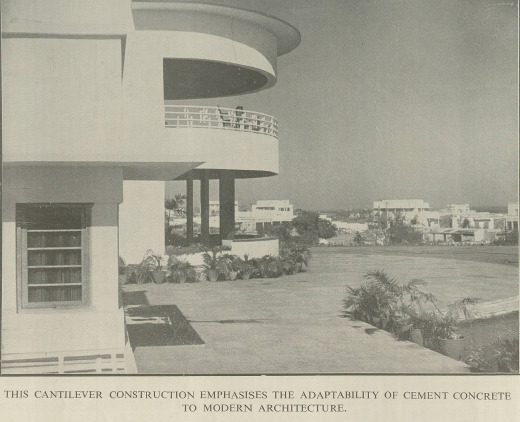

Other advantages that propelled its popularity included durability, strength, and the ability to expand parts beyond the buildings, for instance, to create cantilevers, a common feature seen in modern architectural styles like Art Deco (see Figure 1).[6] As a 1935 issue of the Indian Concrete Journal proclaimed: “In steel and concrete we have the two greatest structural units the world has known – steel in tension, concrete in compression.”[7]

Why RCC in India?

In India, it can be argued that the increased use of RCC over other materials in the twentieth century was primarily due to the country’s prevailing socio-economic conditions. RCC construction had a large scope for unskilled labour.

Apart from processes such as the preparation of the steel reinforcements that required supervision, building with RCC claimed to not require any “special skill.”[8] This combined with India’s abundant supply of cheap labour meant that RCC continues to be the standard choice for large-scale projects in the country over other materials, even today.[9]

Large-scale industries of other building materials in modern India (such as steel) were also experiencing growth at a slow rate. Their development was subject to conditions under colonial rule like import-export rules, tariffs, wages, governmental policies and support for domestic production, and the nationalist (swadeshi) struggle.[10] According to British Structural Engineer and expert Stuart Tappin, the UK and USA’s large steel production facilities meant that it was more economical to build larger-framed buildings with steel rather than concrete.[11] The UK was a pioneering force in the invention and production of steel, while in the US, New York’s Art Deco buildings owed their glitz and shine to the new steel alloys, which arrived due to the technological innovations in the early twentieth century.[12] These included non-corrosive stainless steel alloys like nickel silver, monel, duralumin and “Nirosta” ( seen on the glittering crown of the Art Deco Chrysler building); they were replaced post-World War II with newer, less expensive materials that reflected the changing tastes and styles of the post-war generation.[13]

Additionally, the US was regarded as “the nation of steel,” primarily due to the presence of the skyscrapers in New York and Chicago, while Europe was shown to have a preference for reinforced concrete. While not entirely true (American involvement was an important aspect in the development of reinforced concrete around the world), this perception was due to the reluctance of the US to claim this material. The US was not susceptible to the usage of RCC in the twentieth century, due to doubts about whether it could be considered as an “industrial material.”[14] RCC required craft labour which did not correspond with America’s industrial principle of mass production.[15]

Concrete’s requirement of craft and unskilled labour, along with its perception of traditional or “primitive” origins in mud and clay construction, gave it a complex identity that was neither modern or non-modern. [16]

The post war need for fast and economical construction triggered the need for RCC construction, notes Conservation Architect Vikas Dilwari.[19] While the West went for steel, India’s climate was more conducive to cement which easily replaced lime without changing the rest of the construction technology.[20] A similar case can be made for Miami’s notable Art Deco buildings made of concrete, unlike New York’s skyscrapers which were primarily made of steel. The materials used to create Miami’s Art Deco district were inexpensive due to its origins as a middle-class resort, and also climate-responsive, similar to Mumbai’s Art Deco buildings.[21] They were built in the ‘Tropical Deco’ style, whose features included those adapted to Miami’s environmental conditions (such as a projecting roof plane to shelter the terrace), for which concrete was well-suited. [22]

Despite the plethora of advantages offered by RCC, the Indian cement industry still faced numerous obstacles that prevented it from becoming a large-scale profitable industry. The formation of ACC was proposed as a solution for these issues; it succeeded in its initiative by combining the foremost cement companies in an unprecedented merger.

ACC Changes the Game – F E Dinshaw’s Vision and Rationalisation in the Indian Cement Industry

“What set Mr. Dinshaw apart, however, was his commitment to the idea of merger, his powers of persuasion and his drawing force which made things happen.”[23]

– ACC: A Corporate Saga by Abha Chaturvedi, Anil Chaturvedi and M S Kapur

Origin & Objectives of ACC

However, this promising development was short-lived. Excess supply with inadequate demand, resumption of competition with foreign cement post-World War I, a rate war, and locational disadvantages (both to raw materials as well as markets), led to the liquidation of three factories due to losses. The local cement companies turned to the Tariff Board for protection, which responded by increasing import duties to promote domestic cement.

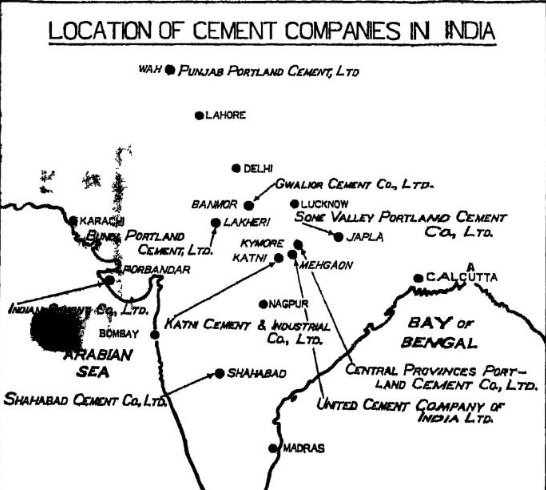

It was at this point that eminent Bombay financier, lawyer, industrialist and the founder of ACC, Framroze Edulji Dinshaw (1872-1936), proposed a merger of the cement plants to counter the issues of the quota system.

A shrewd businessman, who was once the holder of the most directorships in the city, Dinshaw recognised the need to capitalise on the popular material of RCC as well as turn it into a profitable industry. [29]

According to him, the foremost objective of this merger was not to create a “monopolistic” scheme but to provide good quality cement at cheaper rates to the public, against the higher prices of foreign-produced cement, while ensuring a profit margin for Indian cement companies. [30]

Noted businessman Sir Hormasji Pherozshah Mody, the then Chairman of ACC Ltd, stated that ACC was an “outstanding example” of the success achieved through ‘Rationalisation,’ without which it could not have hoped to stabilise the industry. Rationalisation, which began as a movement in 1921, broadly meant the reorganisation of a company to maximise profits, usually entailing the replacement of old machinery with up-to-date ones and release of labour force to increase revenue.[33]

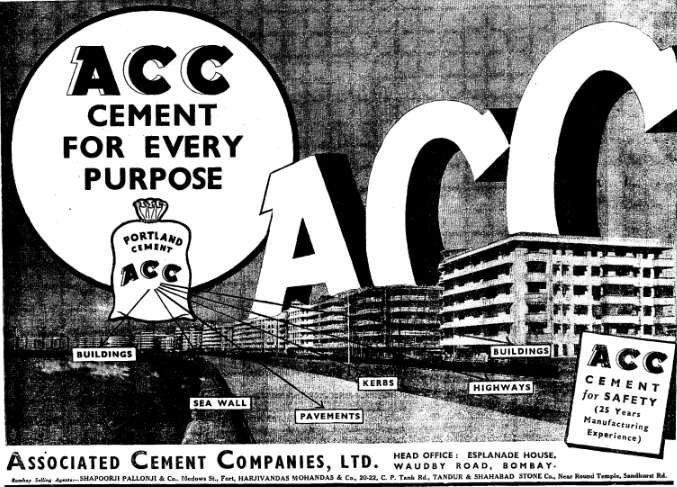

Mody further wrote that under Rationalisation, ACC took measures to regulate production, prices and marketing, set up an efficient technical service and undertook a “country-wide propaganda” for cement as a building material. Since it was a relatively newer material in the Indian construction industry, this propaganda was necessary to make India “cement-minded.”[34]

ACC’s Vigorous Marketing and Propagandising of RCC

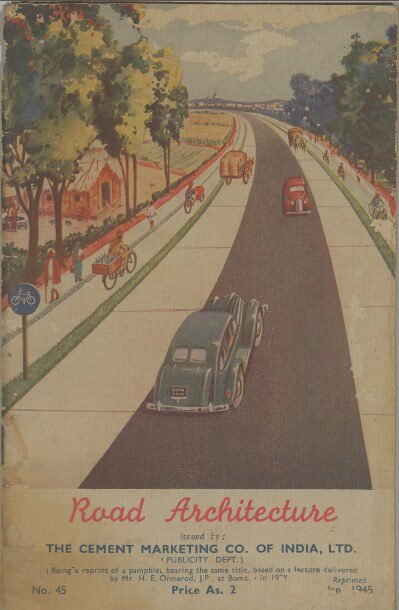

ACC was successful in its nation-wide propaganda, significantly transforming the way cement was marketed to the general public. A prominent way it marketed RCC to the public was through print media. For this, it employed the help of organisations such as the Cement Marketing of India, to produce informational booklets, brochures and guides that were disseminated amongst the masses. These included journals and guides that were more technical in nature, intended for architects, engineers and other building industry professionals (such as The Indian Concrete Journal) as well as simpler guides and catalogues for the general public (such as The Modern House in India, 40, 60 and then 80 designs of buildings for every purpose, You can do this!, etc.).

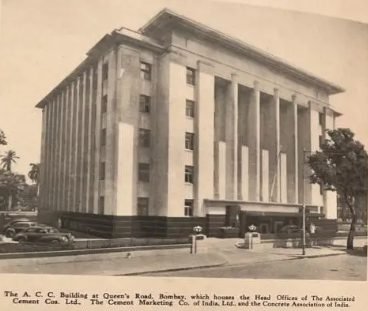

The construction of a new office for the company also became an opportunity to publicise RCC. While the constituent companies’ products were known under their own brand names, there was a need to create ACC’s own identity as a consolidated entity. This involved not just developing a brand name, but also a new office premises.[36] Its new headquarters, ‘Cement House,’ was constructed on Queen’s Road (now Maharshi Marve Marg) opposite Churchgate station, Bombay. Completed in 1943, it is a visually stunning Art Deco structure that flaunted the diverse functionality of RCC; the intricately constructed cantilevered staircase, for example, illustrated the possibilities offered by the construction material in modern design. [37]

By the 1940s, ACC’s reputation as a dominant organisation that shaped Indian construction practices was apparent by the sheer number of significant projects it implemented. Various parts of the lucrative Backbay reclamation region in Bombay for instance, were constructed with ACC’s cement – from the landmark Marine Drive promenade, to the Art Deco buildings lining them (Figure 8).

ACC’s dominance and contribution towards national development continued well into the post independence period, evidenced by the fact that they supplied 14% of the cement used in construction, nationwide.

Criticisms & Shortcomings of ACC

However, there were also some setbacks to the merger. Although the architect of the merger F E Dinshaw did not intend on ACC becoming occupying a monopoly position, it inevitably did so. ACC amalgamated 10 of the 12 cement companies at the time; the 10 companies also belonged to 4 eminent Bombay business groups – the Tatas, Khataus, Killick Nixon and the F E Dinshaw groups.[42] The Tatas occupied a significant position in ACC and the cement industry, with the first successful cement company, Indian Cement Co., being owned by them. After the death of F E Dinshaw in 1936, a couple of months before ACC could be formalised, it was up to J.R.D. Tata to pull off the merger. Though the company’s board of directors contained notable businessmen from Western India like Sir Purshottam Thakurdas, Sir Chunilal Mehta and Ambalal Sarabhai, ACC was undoubtedly “Tata-run and Tata-controlled.”[43] ACC exercised immense influence over policies relating to sales and production of cement, and remained virtually unopposed till it was challenged in part by cement companies from Eastern India such as Dalmia Jain cement (est. 1938).[44]

The cartelisation of the cement companies also came at the cost of a loss of autonomy and individual identity of the merged companies.[45]

Dalmia had refused to join ACC, as it had concluded that there was a discrepancy in the individual companies’ success during the economic depression, with some of the companies doing well, while others experiencing losses; additionally, there was space for more in the industry, and the setting up of a plant was relatively inexpensive.[46] The dangers of cartels, trusts and combines abusing their monopoly and thus sowing “the seeds of Fascism” were recognised in a 1945 issue of the Indian Textile Journal, which also cited the example of anti-trust laws in the US.[47] The process of rationalisation in the industry, which H P Mody had credited in part for the success of ACC, encountered controversies in India’s industries. This included the dilemma of large amounts of labour displacements, particularly in the Indian textile industry, which became a topic for labour protests in India.[48]

While RCC’s functional qualities were heavily promoted, its shortcomings (such as needing maintenance, or the risk of corrosion, termites, etc.), were either inadequately highlighted or ignored. There were also complaints about the quality of the material, mainly due to the lack of supervision of the processes of the material.[50]

Conclusion

“So far as the A.C.C. is concerned, it may be legitimately claimed that the future is safe in its hands; it has the resources, the men and the technical direction which go to the building up of a great industry.”[51]

– Sir H.P. Mody, Chairman of the Associated Cement Companies Ltd., May 1940

A look at the formation and development of ACC Ltd is significant due to its contribution in shaping the modern landscape of India. Its creation introduced a new-found confidence in the nascent cement industry at the time, which had previously suffered from price wars in the mid-1920s and dwindling profits, further exacerbated by the economic crisis of the late 1920s. It accomplished the major objectives for which the merger was created, particularly in making the domestic cement industry. Despite the issues that emerged with the rising prominence of this organisation (such as monopolisation), its impact could not be denied.

RCC’s identity as a ‘modern’ material was one of the primary consequences of ACC’s expert marketing and advocacy. By doing so, it also helped shape the modern architectural identity of the country. The brochures, catalogues and guides published by the company, were not only informative, but accessible, covering every part of India, and reaching out to experts and laymen alike. Their investment in infrastructure development went beyond business interests, extending towards the development of local communities and surroundings; community development became a part of their corporate identity.[54] If ACC had not been formed, it would be safe to say the Indian built landscape would have been markedly different.

By the 1950s, the power balance had shifted from Western countries to India and China when it came to cement production. India reportedly also has the most efficient cement plants in the world.[55]

Today, India is the second largest cement manufacturer in the world behind China, with ACC being the second largest cement company in the country.[56] A major reason behind India’s successful position in the global cement industry can be attributed to the creation and efforts of ACC in the past century.

An unprecedented merger in the twentieth century revived the ailing industry and provided successful alternatives to the way it had functioned till then – it permanently cemented ACC’s position in not only the history of the country’s landscape, but its future as well.

Theertha Gangadharan for Art Deco Mumbai

Theertha is Head, Research & Archives at Art Deco Mumbai. With a background in History, her main interest lies in researching and recording the links between Mumbai’s tangible and intangible heritage, and improving information accessibility in the digital age.

Header Image: Journal of the Indian Institute of Architects, July 1938. Source: Art Deco Mumbai Trust